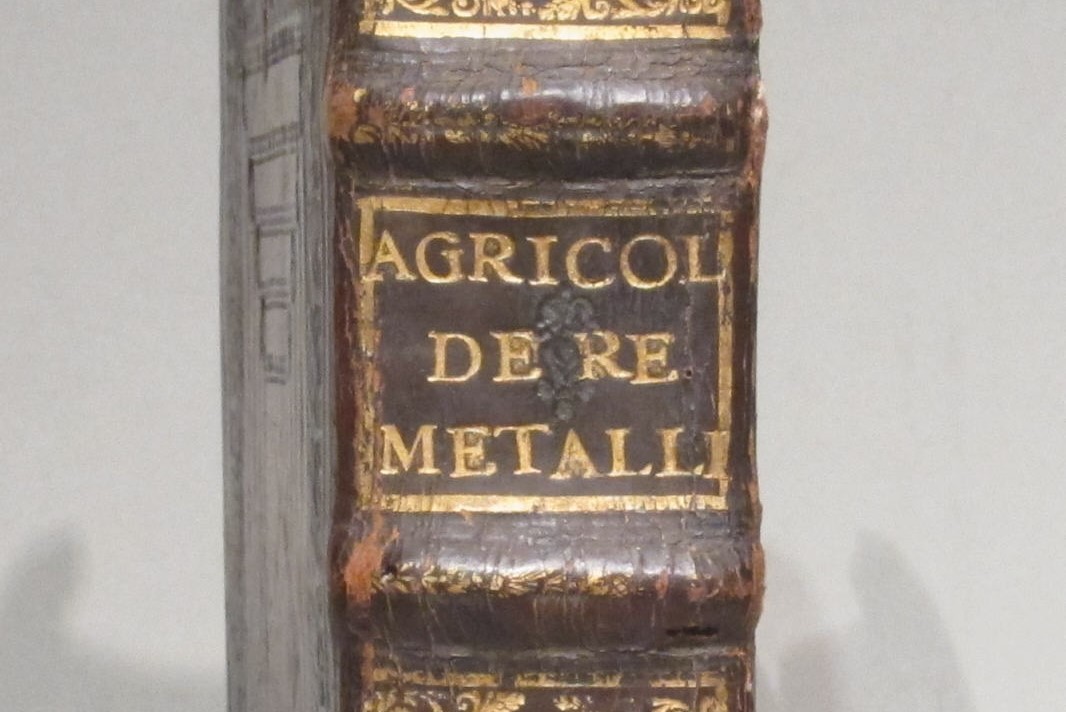

After its publication in 1556, De Re Metallica was considered the authoritative text on the art of mining, refining and smelting metals for almost 200 years.

Written by German scholar Georg Bauer (pen name Georgius Agricola) and published a year posthumously, the text is comprised of twelve books which extensively cover the many different aspects, tools and techniques of 16th century mining.

De Re Metallica provides us with a wealth of insight into the mining industry during the renaissance as well as the culture, legalities, architecture and costume of the time.

This remarkable book contains a huge collection of brilliantly detailed illustrations and technical diagrams, all of enormous historical value.

First edition of De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, 1556. Image source: Milestones of Science Books.

In Book II, Agricola discusses the commonly practised method of locating veins with the use of a 'divining rod'. He takes a sceptical approach to the subject, describing the method and its origins without advocating it.

Although this brief section is of little technical use to the modern day reader, it is certainly fascinating to see wizards, magicians and their incantations presented seriously within the pages of a significant scientific text.

Divining for veins. De Re Metallica Book II, Georgius Agricola, 1556.

"...it seems that the divining rod passed to the mines from its impure origin within the magicians." - Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica, 1556.

Divining for veins. First edition of De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, 1556. Image source: Milestones of Science Books.

The following text regarding the use of divination rods in mining is extracted from Book II of De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, 1556 (translated in 1912 by Herbert Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover):

There are many great contentions between miners concerning the forked twig, for some say that it is of the greatest use in discovering veins, and others deny it. Some of those who manipulate and use the twig, first cut a fork from a hazel bush with a knife, for this bush they consider more efficacious than any other for revealing the veins, especially if the hazel bush grows above a vein. Others use a different kind of twig for each metal, when they are seeking to discover the veins, for they employ hazel twigs for veins of silver; ash twigs for copper; pitch pine for lead and especially tin, and rods made of iron and steel for gold. All alike grasp the forks of the twig with their hands, clenching their fists, it being necessary that the clenched fingers should be held toward the sky in order that the twig should be raised at that end where the two branches meet. Then they wander hither and thither at random through mountainous regions. It is said that the moment they place their feet on a vein the twig immediately turns and twists, and so by its action discloses the vein; when they move their feet again and go away from that spot the twig becomes once more immobile.

"...the twig was retained by the unsophisticated common miners, and in searching for new veins some traces of these ancient usages remain." - Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica, 1556.

First edition of De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, 1556. Image source: Milestones of Science Books.

The truth is, they assert, the movement of the twig is caused by the power of the veins, and sometimes this is so great that the branches of trees growing near a vein are deflected toward it. On the other hand, those who say that the twig is of no use to good and serious men, also deny that the motion is due to the power of the veins, because the twigs will not move for everybody, but only for those who employ incantations and craft. Moreover, they deny the power of a vein to draw to itself the branches of trees, but they say that the warm and dry exhalations cause these contortions. Those who advocate the use of the twig make this reply to these objections: when one of the miners or some other person holds the twig in his hands, and it is not turned by the force of a vein, this is due to some peculiarity of the individual, which hinders and impedes the power of the vein, for since the power of the vein in turning and twisting the twig may be not unlike that of a magnet attracting and drawing iron toward itself, this hidden quality of a man weakens and breaks the force, just the same as garlic weakens and overcomes the strength of a magnet. For a magnet smeared with garlic juice cannot attract iron; nor does it attract the latter when rusty. Further, concerning the handling of the twig, they warn us that we should not press the fingers together too lightly, nor clench them too firmly, for if the twig is held lightly they say that it will fall before the force of the vein can turn it; if however, it is grasped too firmly the force of the hands resists the force of the veins and counteracts it. Therefore, they consider that five things are necessary to insure that the twig shall serve its purpose: of these the first is the size of the twig, for the force of the veins cannot turn too large a stick; secondly, there is the shape of the twig, which must be forked or the vein cannot turn it; thirdly, the power of the vein which has the nature to turn it; fourthly, the manipulation of the twig; fifthly, the absence of impeding peculiarities. These advocates of the twig sum up their conclusions as follows: if the rod does not move for everybody, it is due to unskilled manipulation or to the impeding peculiarities of the man which oppose and resist the force of the veins, as we said above, and those who search for veins by means of the twig need not necessarily make incantations, but it is sufficient that they handle it suitably and are devoid of impeding power; therefore, the twig may be of use to good and serious men in discovering veins. With regard to deflection of branches of trees they say nothing and adhere to their opinion.

"The wizards, who also make use of rings, mirrors and crystals, seek for veins with a divining rod shaped like a fork;" - Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica, 1556.

First edition of De Re Metallica by Georgius Agricola, 1556. Image source: Milestones of Science Books.

Since this matter remains in dispute and causes much dissention amongst miners, I consider it ought to be examined on its own merits. The wizards, who also make use of rings, mirrors and crystals, seek for veins with a divining rod shaped like a fork; but its shape makes no difference in the matter, - it might be straight or of some other form - for it is not the form of the twig that matters, but the wizard's incantations which it would not become me to repeat, neither do I wish to do so. The Ancients, by means of the divining rod, not only procured those things necessary for a livelihood or for luxury, but they were also able to alter the forms of things by it; as when the magicians changed the rods of the Egyptians into serpents, as the writings of the Hebrews relate, and as in Homer, Minerva with a divining rod turned the aged Ulysses suddenly into a youth, and then restored him back again to old age; Circe also changed Ulysses' companions into beasts, but afterward gave them back again their human form; moreover by his rod, which was called "Caduceus," Mercury gave sleep to watchmen and awoke slumberers. Therefore it seems that the divining rod passed to the mines from its impure origin with the magicians. Then when good men shrank with horror from the incantations and rejected them, the twig was retained by the unsophisticated common miners, and in searching for new veins some traces of these ancient usages remain.

"...it is not the form of the twig that matters, but the wizard's incantations which it would not become me to repeat, neither do I wish to do so." - Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica, 1556.

But since truly the twigs of the miners do move, albeit they do not generally use incantations, some say this movement is caused by the power of the veins, others say that it depends on the manipulation, and still others think that the movement is due to both these causes. But, in truth, all those objects which are endowed with the power of attraction do not twist things in circles, but attract them directly to themselves; for instance, the magnet does not turn the iron, but draws it directly to itself, and amber rubbed until it is warm does not bend straws about, but simply draws them to itself. If the power of the veins were of a similar nature to that of the magnet and the amber, the twig would not so much twist as move once only, in a semi-circle, and be drawn directly to the vein, and unless the strength of the man who holds the twig were to resist and oppose the force of the vein, the twig would be brought to the ground; wherefore, since this is not the case, it must necessarily follow that the manipulation is the cause of the twig's twisting motion. It is a conspicuous fact that these cunning manipulators do not use a straight twig, but a forked one cut from a hazel bush, or from some other wood equally flexible, so that if it be held in the hands, as they are accustomed to hold it, it turns in a circle for any man wherever he stands. Nor is it strange that the twig does not turn when held by the inexperienced, because they either grasp the forks of the twig too tightly or hold them too loosely. Nevertheless, these things give rise to the faith among common miners that veins are discovered by the use of twigs, because whilst using these they do accidentally discover some; but it more often happens that they lose their labour, and although they might discover a vein, they become none the less exhausted in digging useless trenches than do the miners who prospect in an unfortunate locality. Therefore a miner, since we think he ought to be a good and serious man, should not make use of an enchanted twig, because if he is prudent and skilled in the natural signs, he understands that a forked stick is of no use to him, for as I have said before, there are the natural indications of the veins which he can see for himself without the help of twigs. So if Nature or chance should indicate a locality suitable for mining, the miner should dig his trenches there; if no vein appears he must dig numerous trenches until he discovers an outcrop of a vein.

Source: www.gutenberg.org

De Re Metallica is available to read online in its entirety, and is definitely worth a look even if for the illustrations alone.

SEE ALSO

PROSPECTORS AND MINERS ASSOCIATION VICTORIA

Established in 1980, the Prospectors and Miners Association of Victoria is a voluntary body created to protect the rights and opportunities of those who wish to prospect, fossick or mine in the State of Victoria, Australia.

You can support the PMAV in their fight to uphold these rights by becoming a member. You'll also gain access to exclusive publications, field days, prospecting tips, discounts and competitions.

Check out the PMAV website for more information.

Established in 1980, the Prospectors and Miners Association of Victoria is a voluntary body created to protect the rights and opportunities of those who wish to prospect, fossick or mine in the State of Victoria, Australia.

You can support the PMAV in their fight to uphold these rights by becoming a member. You'll also gain access to exclusive publications, field days, prospecting tips, discounts and competitions.

Check out the PMAV website for more information.