The discovery of gold in Victoria was officially announced in July, 1851, and with great excitement the colony's rich goldfields were opened up one by one.

The incredible alluvial fields of Ballarat, Mount Alexander and Bendigo were all brought to light by the end of 1851, and in 1852 the gold rush was in full swing.

People were coming from all over the colonies, and soon the world, to try their luck drawing fortunes from the rich Victorian ground. Some saw success beyond their wildest dreams, others went home cursing the lottery fields which had brought them nothing but misery, but one thing was certain - society was stricken beyond hope with gold fever.

In 1853 the deep ground of Ballarat began to reveal treasures which inspired awe all over the world. One by one, great nuggets were pried from the ancient riverbeds which lay hiding below, guarded by seemingly endless feet of wet and dangerous drift. The world got a glimpse of the potential of Victoria's goldfields, and it was only just the beginning.

More and more rich fields were discovered, with thousands of diggers rushing from place to place in a frenzy, envisioning pockets of treasure at the bottom of every hole.

While all this madness was going on, an old hand named William McLachlan was employed as a shepherd's hut keeper all the way out on the Concongella pastoral run1, about 80 miles beyond Ballarat, and far beyond the scope of any known goldfield.

McLachlan had arrived in Van Diemens Land on the Convict ship Competitor way back in the 1820s.2 He had been in the colonies for the birth of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, the establishment of the Colony of Victoria, and the onset of the great Victorian gold rush in 1851.

Prior to his employment at the Concongella run, McLachlan had spent some time at Buninyong, one of Victoria's first discovered goldfields, and he knew a bit about prospecting for gold. 3

So there he was in 1853, perched on the bank of Pleasant Creek, peering into his cooking dish which he was using as a gold pan.4 And a small, but beautiful show of colour was shining back at him.

Although it wasn't much, McLachlan's discovery would soon lead to the opening up of one of Victoria's most prominent quartz mining fields, which is still yielding gold to this day.

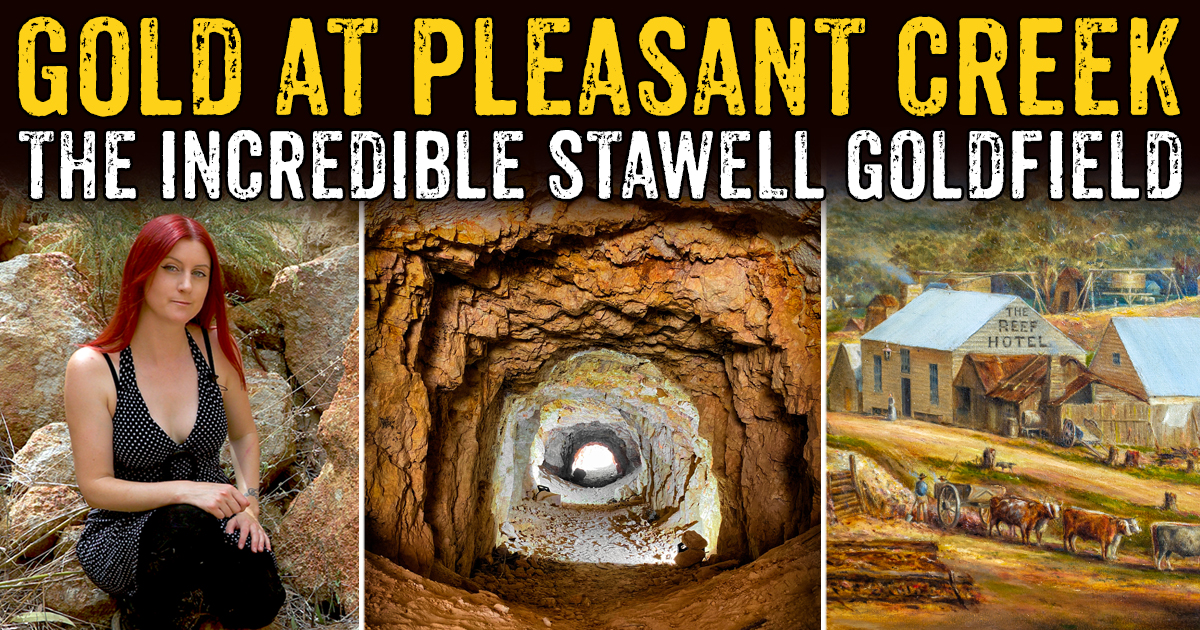

In this video, we're going to take a look at the brilliant gold mining history of Stawell!

You can watch the video below, or scroll down to keep reading.

I'm here at Pleasant Creek, and along the creek behind me is the spot where McLachlan first got a glimpse of that gold in his cooking dish.

The rush here was fairly small - in fact, it took a while before things really kicked off - but over the next few years, further discoveries in the area would lead to great rushes.

In 1856 a fella named Charles Broad and his mates were digging at Forty-Foot-Hill, a few miles from the site of McLachlan's original gold discovery,5 where they sank the first deep hole on the field6 They bottomed on rich alluvium - leading to the famous Commercial Street rush.

Another big rush soon followed out at Deep Lead, and more discoveries continued to come to light over the next few years. The mid to late 1850s saw the wild and peaceful bushland of Pleasant Creek transformed into a hive of activity and a myriad of settlements.

These places were all yielding alluvial gold, which is gold that has been washed away from its original source by water and gravity. So, where was it all coming from?

Well, it was washing down from the reefs! Gold had been discovered in the quartz outcrops on Big Hill in 18557 and although the difficult nature of working quartz for gold by hand hindered any major rushes to the reefs in those early years, there were a few who worked there with persistence. And it was in the quartz reefs where the Stawell goldfield would really shine!

In 1855, two parties made their way up to the quartz outcrops on the western slope of Big Hill. The first party, mates Sloane and Guppy, were getting some great colour in their quartz, but without any crushing machinery they just couldn't keep at it.

The second party, Donnelly, Duncan, Proctor and Beechner, were working close by and struck a particularly rich vein, becoming the first party to strike payable gold up in the quartz reefs. Word soon spread, and before long folks were arriving at the reefs from diggings nearby.8

But what good was all this rich quartz if there was no way of crushing it? They couldn't just keep smashing it up by hand if they ever hoped to make a profit.

Something had to be done, so Donnelly journeyed to Kingower to purchase a hand-powered berdan pan,9 a machine which reduces quartz using heavy iron balls. Combined with a hand-powered stamper,10 this rudimentary crushing machine, however inefficient, was a huge step forward in the development of the quartz mining field on The Reefs at Pleasant Creek.

Along his journey to Kingower, Donnelly had camped beside a fella named Wainwright and shared glowing reports of the rich quartz on Big Hill. Wainwright took these reports back to his mates at St Arnaud, who formed a party and headed for Pleasant Creek.11

This party consisted of Dane, Blundell, Gutierrez, and Wainwright. It was Dane who pitched one of the first tents at the reefs,12 giving the field its first sense of permanency, and it was Dane who put the first lot of quartz through Donnelly's crushing machine, with an incredible yield of about 50 ounces to the ton!13

Dane's party quickly decided to get their own Berdan crusher, which they had set up before the end of 1856.14 By this time there were thousands of diggers on the Pleasant Creek field, most working the alluvial fields, but some working up on the quartz reefs as well.

These hand powered crushers enabled quartz to be properly sampled, and brought a profit from rich quartz, but the slow and arduous nature of the work was simply not sustainable. Quartz was being roasted, broken up by hammers, further reduced by the crude stamper, then fed into the hand-powered berdan pan for a final crushing.15 This was a slow process, and the machine could only handle small amounts of quartz at a time.

Without more efficient crushing machinery, all that most of the diggers at The Reefs could do with their quartz was set it aside in stockpiles and wait.16 Many of the diggers at the alluvial rushes were in the same predicament, as much of their gold lay trapped in a hard cement, or conglomerate,17 and there it would stay until the stuff could be crushed.18

They didn't have to wait too long - around early 1857, Grant, Lamont and Company erected a horse powered Chilean mill on Concongella Creek, and started crushing for the diggers.19 They charged a hefty price! But it was a very welcome development on the field.

A Chilean mill is a machine which crushes stone by rolling large heavy wheels around in a circular basin, and these were powered by either horses or steam.

Grant, Lamont and Company's mill consisted of three pairs of Chilean rollers, which were driven by an old-fashioned beam engine.

The introduction of this machine to the Pleasant Creek goldfield allowed the diggers to start processing their stockpiled quartz and conglomerate,20 and the introduction of a second machine down at the Commercial Street rush, and a third at Concongella Creek,21 created competition, resulting in a reduction of crushing costs.22

The quartz reefs were then taken on with a whole new level of enthusiasm. By the end of the 1850s the whole area of the quartz reefs had been taken up by small parties. As the great alluvial rushes at Pleasant Creek receded, the quartz miners remained steady at work. 23

But what about the town?

When a township was surveyed here in 1858 Pleasant Creek was given the official name of Stawell, named after Sir William Foster Stawell. The town was set out along Pleasant Creek near the site of McLachlan's first gold discovery, and a number of stately Government buildings were established. But the neat new town had a curious feature - nobody wanted to live there! The population largely lived and worked at the diggings, and had no reason to relocate to the newly surveyed township. Main Street up near The Quartz Reefs continued as the main center of the area.

The 1860s saw many small parties working together, forming small companies and combining their capital to manage the expenses of mining and much-needed machinery.24 Stawell's first public company was registered in 1861 - The Pleasant Creek Quartz Mining Company25 - and many more soon followed.

The man-powered windlass gave way to more efficient horse-powered whips and whims, and in 1860 the first steam-powered winding engine on the field was operating at the Great Northern mine.26 Steam power was the way forward, and in 1862 there were almost ten engines operating at Stawell.27 It wasn't long before winding engines and their poppet heads began to dominate the landscape.

As well as the improvements in winding machinery, there was a great improvement in crushing methods as well. The first hand powered Berdan crushers had quickly been superseded by horse and steam powered Chilean mills, and before long, stamp batteries were introduced to the area.

The first battery at Stawell was put up at the Great Northern mine, and was a Cornish style battery. It had square stamps, and a cam barrel made from a redgum log, instead of the typical cam shaft of a Californian style battery.

More and more of these machines were introduced.

These machines allowed quartz to be crushed in much greater volumes, at far better prices, and importantly, they made expensive underground development a much more viable option.28

By the mid 1860s there were almost 300 claims on the field,29 and underground mining at the reefs had extended to a depth of 500 feet.30

As mining operations grew, so too did their expenses, and the small companies simply couldn't keep up. Many of them amalgamated with their neighbours, brought in new investment, and worked the larger areas of ground more efficiently from a single shaft. By 1870, the huge number of claims that were originally opened up along the lines of reefs had been reduced by amalgamation to a few dozen large companies.31

Over time, these companies upgraded their machinery, explored deeper underground, and extended their drives along the reefs beneath the town.

The 1870s was a decade of prosperity at Stawell, as year after year incredible amounts of gold were raised from underground.32 Statistics relating to the mines at Stawell were shared by the Mining Department towards the end of 1879 - the total yield of gold up to that time was over a million ounces, at an average of just over an ounce per ton, and over two and a half million pounds had been paid in dividends. There were 31 steam engines, 256 stamp heads, 48 whims and 10 whips on the field. The richest recorded sample of quartz was obtained near the surface in Sloane's Flat Reef, where one bucket yielded an incredible 60 ounces of gold.33 In summary, the Stawell goldfield was going very well.

But it often came at a great cost. Mining was fraught with dangers, and Stawell, like most goldfields, saw its share of cave-ins, explosions, floods, and falls.

One particular incident really stands out, and we're going to take a look back to the year 1873, when five men were working a very risky shift underground in the Darlington Company mine.

The Darlington Company was working here about four miles from Stawell. They had recently put down a new shaft and they wanted to connect with the nearby workings of their old shaft, where payable quartz had been discovered some months earlier. As there had been no pumps operating at the old workings for some time, they had filled with a great body of water which would need to be removed.34

Rather than run expensive machinery at the old shaft to pump the water out, they devised a plan - from their new workings, they would put in a jump-up to get to the right level, and drive over to the old workings. When they got close, they would put out a bore in order to tap the flooded mine and let the water out at a manageable rate.35 The water would gradually flow back down the drive and into the well of their main shaft, where it would then be lifted to the surface by the mine's powerful pump.

What could possibly go wrong?

Of course, the company knew this was a risky venture, and were taking every precaution they could think of to avoid catastrophe.

As the drive approached the old workings, as determined by surveys, the company stopped work in the lower levels of the mine, knowing that if even a small burst of water came in, the miners could not all be brought up fast enough in the cage before the lower levels were flooded.36

A drill was used to bore four feet ahead for the last 20 feet of driving in order to tap the water, and strict orders were given to keep the drill hole clear at all times. The ground was timbered securely as soon as it showed the slightest hint of instability, and lights were kept burning along the drive to help the men get out quickly if they needed to.37

But it wasn't enough. The Darlington Company mine would shortly become the scene of Stawell's most terrible mining accident.

On Thursday 23rd of January, 1873, they were getting very close to the flooded workings. The men working underground got a bad feeling and came to the surface as they considered the ground to be unstable. They were afraid the water would burst through, and the mining manager, Watson, sent them home.38

The next day, Friday the 24th, manager Watson and four others - Stafford, Reed, Armstrong and Porter - went down below to inspect the ground in the jump-up, and to timber the ground near the face.39

They spent the morning timbering and everything seemed alright when they stopped and headed for the surface for dinner. After their break, Watson, Porter, Armstrong, and Stafford went down below again, while Reed stayed up top making battens to bring down. Before long, Reed brought them below and up to the face. He had nailed three of them on, when he said he thought there was more water coming in. Watson looked at the face and couldn't notice any increase. Reed insisted, so Watson said come all down.40

They climbed down out of the jump up and sat smoking for five or ten minutes. Reed, who had noticed the increase in water, said that if he only had the other batten nailed on he would be satisfied, and that he would go back up and put it on.41

The manager Watson said not to mind, but that if Reed was going, he would go up with him to measure the exact distance the jump up had been driven. Watson sent Porter to the surface for a tape line so he could do just that, but when Porter returned, Reed quickly took the tape line and went up the jump up with Stafford and Armstrong, leaving Watson and Porter waiting in the drive below.42

A knocking echoed down from the jump up, the sound of nails being driven. After a time, Porter was preparing to go to the jump up and call the men down, when suddenly...43

Watson yelled to Porter to run for his life to the shaft, and they rushed to the cage.44

The water was there almost instantly, and looking back they saw it coming upon them in a great body four or five feet thick.45

The two terrified men climbed up on top of the cage, thinking that some of the others might be washed by the water down the jump-up and into the shaft, and might be able to get on to the cage. They waited to give the signal to wind up until the water was about 6 or 7 feet up the shaft. The water was over Porter's head when he finally rang the bell.46

But the cage got jammed, and the force of the water sent the two men about 90 feet up the shaft. When the cage cleared itself, Watson and Porter were raised to the surface clinging to the rope some distance above the cage - which came up empty. None of the others had made it to the shaft.47

The town was in shock. It took days to recover the bodies of Armstrong, Reed and Stafford. The pumps were kept going at the longest stroke, while the water was also bailed using large canvas bags.48 Every day the mine was busy with distressed visitors, wanting to know details about what had happened, offering assistance, and waiting for the recovery of the three unfortunate men.49

After much difficulty, one by one the broken and battered bodies were brought to the surface, inquests were held, and the men were laid to rest.

The newspapers reported that all three of the unfortunate men had shared presentiments of their terrible fate, and that on the morning of the accident, while leaving home, Stafford had turned back several times to kiss his younger children and wish them farewell.50

Unfortunately mining accidents were all too common, and even after the introduction of the Regulation of Mines Act, dangerous practices continued. In 1875, miners working at the Magdala were reportedly still standing on the edge of a huge kibble bucket, holding onto the winding rope as they were lowered 1600 feet underground.51 But even when mines operated most carefully, there was always the risk of disaster.

Between 1857 and 1939, over 500 mining-related accidents were reported in Stawell and surrounding districts.52

But work goes on. The mines at Stawell continued through the prosperous 1870s - a prosperity which had certainly attracted the attention of outside investors. A decline in underground alluvial mining at Ballarat had freed up capital for the mines at Stawell.53 Many Ballarat investors were putting their money into Stawell mines, and Ballarat miners were pouring into the district.

But not all these outside investors had the best intentions, and a few were looking at some of the rich claims at Stawell with coveting eyes.

Rich yields of some of the claims on The Reefs had attracted great attention to the neighbouring claims, some of which were being held and not worked - a practice called "shepherding".54

Most of the best claims along the reefs in 1872 were held under Miners' Rights, and were subject to the Bye-Laws of the District Mining Board - one of which provided protection regarding labour covenants to claims where £1,000 or more had been expended. These claims were so well protected under the Miners' Right that if someone wanted to be put in possession of a shepherded claim, it was only subject to forfeiture if the owners failed to comply with ordinary working conditions after recieving a full weeks notice.55

But this was not entirely watertight, as Stawell miners would soon see.

A party of scheming Ballarat speculators formed an associated propietary which they called the "Pleasant Creek Jumps" 56 - which is a rather obnoxious name - and they hired the very best lawyers to assist them in jumping, or taking over, several claims on the reefs at Stawell.

Over the previous few years, believing that some of the shepherded claims were liable to forfeiture, some Stawell claimholders engaged in a series of what were called "friendly suits" at the Wardens Court, transferring the claims to trusted friends, who then transferred them back,57 making each a claim a new holding - they were strarting fresh.

But, as the original claims had expended far more than £1,000, they were protected under the bye-laws all along, and there was no need for any of these friendly suits - and what's more, by doing this, they had in fact unknowingly deprived themselves of that protection.58

On top of this, some of the new claims which had resulted from the friendly suits had not been properly taken possession of as required by the bye-laws of the district, and these claims were therefore deemed to be occupied illegaly.59

The Ballarat speculators believed they were entitled to take possession of these claims by virtue of their miners' rights.60

This came as a great shock to the claim-holders at Stawell, but they had no intention of giving up quietly - there was a lot at stake! The claims in question along the Scotchmans, Sloanes and Cross Reefs were some of the highest yielding on the field, and the claimholders were some of the town's largest mine owners.61

J. W. Guttierez, one of the earliest pioneers on The Reefs, was quoted saying "We must tell the damn jumpers that we'll have none of em, and they'll be tarred and feathered if they come here".62

A series of persistent applications and appeals by the Ballarat jumpers came before the Wardens Court over several months, and were all ruled in favour of the original claim holders at Stawell - until on one of them, the Judge agreed to 'state a case' for Judge Molesworth, the Chief Judge in Mining. He explained that although the original claimholders had established possession, they had deprived themselves of the right to claim protection from forfeiture by entering into those 'friendly suits'. This gave the Ballarat jumpers renewed enthuseasm and ammunition for their cause, and even more applications were put in for claims at Stawell.63

The Pleasant Creek Jumps had engaged some of Victoria's very best lawyers, and they won every case. They then sought to physically take over the claims by sending men to put in new boundary pegs.64

The Stawell claim-holders employed local men to watch over the mines and guard the corner pegs, day and night.65 Things were getting very heated at Stawell.

They were advised to quickly take out mining leases on their ground. The claims in question at this point were Nos. 10 and 11 North Perthshire, No. 4 North Scotchmans, and Nos. 2, 6, 7 South Cross Reef, all of which had been given to the Pleasant Creek Jumps on appeal from the Wardens Court. 66

But there was a partial success! Leases were approved to the Stawell claim-holders for all of these claims - except the two North Perthshire claims and the No. 4 North Scotchmans.67

Of course, this was contested again by the Stawell claim-holders.

The town was filled with excitement, and for weeks groups of men were stationed at every boundary peg, with the intention of resisting any attempt at re-pegging.68

After a lengthy period of litigation and high tension over 1872 and 73, the final appeal was finally heard - and in a crowded court room filled with excitement, the judge ruled in favour of the jumpers.69

The jumpers re-registered No 4 North Scotchmans70, but in order to take possession, the Pleasant Creek Jumps still needed to put in new boundary pegs. A group of men from Ballarat had arrived in Stawell with their pegs71 and twenty five policemen, armed with Lee Enfield rifles and bayonets, had been sent to Stawell from Melbourne in order to keep the peace.72

A mob of three or four hundred locals swarmed the disputed ground,73 prepared to physically resist the jumpers.

At midday on the 2nd of August, 1873, two men Bickett and Sleeman, acting as agents for the jumpers, were escorted by the Mining Warden and a large body of police onto the No. 4 North Scotchmans. Groups of miners guarded every peg using passive resistence, but one by one, after much crowding, pushing and jostling, the police managed to make enough room for the two men to remove the old pegs and drive in their own. At the fifth and final peg, it was reported that a very determined yet well respected citizen displayed such a formidable resistence that he managed to thwart the efforts of a fully armed body consisting of 8 troopers and 30 foot police. Police reinforcements were sent for twice, and it was only after the troopers had charged through the crowd and formed a ring around the jumpers' agents that the last peg was finally driven into the ground - after some very rough handling.74

The Jumpers' agents were quickly escorted from the scene, but were thoroughly mobbed, stoned and abused on their way out.75

When three of the jumpers' agents arrived at the claim a few days later to mark out a new shaft site, a large crowd snatched their tools from them and ran them off the ground.76

Over the next few months, charges of assault and conspiracy to riot were brought against several Stawell locals, but were all dismissed in court, a decision which was greatly celebrated in the town.77

In a twist of fate, the only claims the Pleasant Creek Jumps managed to snatch, after all that fuss in court and all the violent business with the boundary pegs, were described by Maynard Ord as being "but barren successes".78 The invading jumpers toiled in vain while many mines around them were raising fortunes. Some may say they got what they deserved.

The prosperous 70s went on - but the prosperity wasn't for everyone. There was, of course, the matter of the continually failing Magdala mine.

The Magdala company was formed in 1868 to explore the ground alongside the Oriental mine. The Oriental had been doing extremely well, and it was hoped that there would be a continuation of that success in the Magdala claim.79

So the company set to work! The shaft was sunk, and while it passed through several flat reefs, none were payable. They passed through another reef at 1663 feet, also not considered payable, and they continued sinking, with continued disappointment.80 Determined to strike the rich ore they knew must be hiding somewhere, they sank deeper, and deeper, until in 1880, they had reached the remarkable depth of 2,409 feet.81 Through their persistence, the Magdala mine boasted the deepest shaft in Australia. The company held onto this record for nine whole years, until Bendigo's quartz King George Lansell overtook the Magdala by a few hundred feet with his 180 mine, sinking to a depth of half a mile.82

But for all this work the Magdala still had nothing to show for it. All there exploration and driving continuously proved nothing but unpayable ground.83

After spending £123,000 of shareholders money, the Magdala company was wound up in 1883.84

The Magdala lease and plant was purchased by Thomas Kinsella and Mary Hobbs - the owners of the neighbouring Moonlight mine, and the first order of business was amalgamation! They combined the two companies and formed the Magdala-cum-Moonlight, a private company in which they were the only two shareholders. They set to work in the Magdala ground, crosscutting to the east, and soon came upon a 20 foot thick orebody which was yielding two ounces to the ton. This was Stawell's now famous Magdala lode - and it turned out, it was the very same reef which the Magdala company had passed through at 1663 feet, which had appeared to be unpayable.85

Kinsella and Hobbs had uncovered an absolute fortune in their newly aquired mine. And most of the work had already been done for them!

Although the Magdala shaft had reached the phenomenal depth of 2,409 feet, Kinsella and Hobbs barely needed to bother with it below a depth of 1405 feet. Incredibly, they never needed to sink an inch further, and barely explored any new ground. They just took out the reef they'd come upon from the 1405 feet level upwards. And I mean they really took it out. They removed every inch of the quartz they blasted, leaving nothing behind, taking out practically all the stone between the walls, regardless of grade. They raised every bit of it to the surface and put every last speck through their battery.86

The great stopes underground were propped up by great tree trunks, and before long the huge caverns where quartz had been taken out were like a forest of timber underground.87

The Magdala-cum-Moonlight soon became legendary among the Stawell mines, and while their average yield was generally low due to crushing all the quartz indiscriminately, their rich patches paid them very well.

Over two decades, the company paid £357,750 in dividends88 - not bad at all, when you consider that huge sum was split between only a few shareholders!

The Magdala-cum-Moonlight was not the only success story on the quartz reefs at Stawell - the Oriental crushed the richest stone in the field,89 and the Pleasant Creek Cross Reef was the biggest gold producer.90 And these were just the most notable. There were many mines along the reefs at Stawell which did extremely well.

The mid 1890s saw a decline in the mining industry, but it wasn't over yet! The introduction of cyanide treatment called for the re-processing of many tons of crushed battery sands, and in 1897, Stawell Amalgamated Scotchmans built the biggest cyanide plant in Victoria.91

But, all good things must come to an end, and in the late 1890s Stawell's only significant gold producers were the Magdala-cum-Moonlight and the Sloanes and Scotchmans.92

Thomas Kinsella was one of the driving forces in the field's prosperity - he had made a fortune with the Magdala-cum-Moonlight, but he also invested heavily in other mines, keeping them operating long after they became unpayable.93

Both owners of the Magdala-Cum-Moonlight mine, Kinsella and Hobbs passed away in 1902, and when Kinsella went, the drive in management went with him.94 This coincided with a rapid decline in the mine's output. The company did not pay any further dividends after 1902.95

The mine soon lay idle and the neighbouring Sloanes and Scotchmans company eventually purchased it for £8000 and worked the ground just over the boundary from their own lease.96

The early 20th century had seen Stawell's remaining great mines closing down one by one, until finally there was only one left - the Sloanes and Scotchmans United. In 1920, the company wound up,97 marking the end of a great era at Stawell.

While the town's famous quartz mines had all closed down, small mining operations continued at Stawell through the early 20th century.

There's a very interesting relic of 20th century mining you've got to see. I mentioned horse powered Chilean mills earlier, and theres a brilliant example hiding out in the bush on private property, which I'd love to show you.

This quartz crushing mill was operated in the 1930s. Now as you know, this mill is supposed to be a huge heavy wheel which is rolled around this circular pit to crush the ore. We can see that wheel in these photos from the 1980s. This very wheel has been preserved, and is now on display over at the town's museum - in fact there's a lot of incredible stuff on display there.

Set in the old court house, the Stawell Historical Society and Museum is a must-see when visiting the town, and is located right alongside the visitor information centre. As well as detailed mining models, tools, and other fascinating relics, they've got this incredible panorama along the wall, taken in 1874! The detail in this is remarkable. If you look closely, you can even see a miner lying alongside a shaft talking to his mate down the bottom.

While you're there, be sure to head around the back to check out the old police lock up, and this small six-head stamp battery which was made by G. Kay and Co of Stawell.

Stawell is a brilliant destination to explore if you're interested in learning about gold mining history. Remnants of the town's mighty quartz mines still stand throughout the town, with beautiful old brick machinery foundations marking the sites of winding engines, stamp batteries and more. These were constructed using Stawell bricks, made from Stawell clay. The impressive chimney stack of the old brickworks is an iconic feature. And to this day the same style of bricks are still being made from local clay on the very same site.

Mining machinery is proudly displayed around the town, there are several monuments commemorating the district's gold-seeking pioneers, and last but not least. There's a fantastic educational lookout over the town's operating gold mine!

Here you can get an up-close look at some of Stawell's unique geology, and learn about the many fascinating processes involved in extracting gold from ore.

As you can see, Stawell's remarkable gold mining heritage is still alive today!

I wonder if William McLachlan had any idea the magnitude of the goldfield he had uncovered when he first spotted that colour in his cooking dish here at Pleasant Creek over 170 years ago.

One thing I do know - the story is certainly not over yet!

I'd like to say a huge thank you to the folks at the Stawell Historical Society for their help and hospitality throughout the production of this video.

If you'd like to learn more about the history of Stawell, be sure to stop by the Stawell Historical Society and Museum, where you'll find a wealth of information, books, and historical treasures.

Thanks for watching this video. If you're interested in the fascinating history of the Victorian Goldfields, don't forget to subscribe! and turn on notifications.

1 The Golden Years of Stawell, p9

2 www.convictrecords.com.au

3 The Golden Years of Stawell, p9

4 Shepherd's Gold, p2

5 Shepherd's Gold, p4

6 The Golden Years of Stawell, p9

7 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p258

8 Shepherd's Gold, p22

9 Stawell: Past and Present, p24

10 The Golden Years of Stawell, p10

11 Stawell: Past and Present, p24

12 Shepherd's Gold, p22

13 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p43

14 Shepherd's Gold, p23

15 Stawell: Past and Present, p25

16 Shepherd's Gold, p30

17 Stawell: Past and Present, p10

18 Shepherd's Gold, p31

19 The Golden Years of Stawell, p10

20 Shepherd's Gold, p31

21 Shepherd's Gold, p31

22 The Golden Years of Stawell, p11

23 The Golden Years of Stawell, p13

24 Shepherd's Gold, p32

25 The Golden Years of Stawell, p28

26 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p258

27 The Golden Years of Stawell, p24

28 The Golden Years of Stawell, p24

29 Shepherd's Gold, p31

30 The Golden Years of Stawell, p25

31 Shepherd's Gold, p32

32 The Golden Yeras of Stawell, p62

33 Underground Survey Maps of the Principal Mines at Stawell, SLV

34 Stawell: Past and Present, p31

35 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

36 Pleasant Creek News 1/2/1873

37 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

38 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

39 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

40 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

41 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

42 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

43 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

44 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

45 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

46 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

47 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

48 Pleasant Creek News 28/1/1873

49 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

50 Pleasant Creek News 30/1/1873

51 The Golden Years of Stawell, p88

52 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p257

53 The Golden Years of Stawell, p37

54 Shepherd's Gold, p98

55 Stawell: Past and Present, p118

56 Stawell: Past and Present, p118

57 Shepherd's Gold, p98

58 The Argus, 8/4/1873

59 The Argus, 8/4/1873

60 The Argus, 8/4/1873

61 Shepherd's Gold, p101

62 Shepherd's Gold, p100

63 Shepherd's Gold, p101

64 Shepherd's Gold, p102

65 Shepherd's Gold, p101

66 Shepherd's Gold, p102

67 Shepherd's Gold, p102

68 Stawell: Past and Present, p119

69 Shepherd's Gold, p103

70 Shepherd's Gold, p103

71 Shepherd's Gold, p103

72 Shepherd's Gold, p104

73 Shepherd's Gold, p104

74 Shepherd's Gold, p104

75 Shepherd's Gold, p105

76 Shepherd's Gold, p105

77 Shepherd's Gold, p105

78 Stawell: Past and Present, p119

79 Shepherd's Gold, p150

80 Shepherd's Gold, p151

81 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p173

82 The Age, 21/9/1889

83 Shepherd's Gold, p151

84 Shepherd's Gold, p151

85 Shepherd's Gold, p152

86 Shepherd's Gold, p152

87 Shepherd's Gold, p153

88 Shepherd's Gold, p152

89 Shepherd's Gold, p154

90 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p126

91 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p258

92 Shepherd's Gold, p155

93 Shepherd's Gold, p156

94 Shepherd's Gold, p157

95 The Golden Years of Stawell, p142

96 Shepherd's Gold, p157

97 The Gold Mines of Stawell, A Pictorial History, p258

images, maps and plans used in the video

- Cradling. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- Tin Dish Washing. S.T. Gill. 1869. State Library Victoria

- Golden Point, Ballarat. Thomas Ham. 1852. State Library Victoria

- Forest Creek, Mt. Alexander. Engraved by Thomas Ham. 1852. State Library Victoria

- Zealous gold diggers, Castlemaine. S.T. Gill. 1852. State Library Victoria

- Bad Results. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- Fossicking. S.T. Gill. 1852. State Library Victoria

- The License Inspected. S.T. Gill. 1854. National Library Australia

- Invalid Digger. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- Lucky Diggers on way from Bendigo 1852. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- Ballarat Township Reserve, W.S. Urquhart. 1852. PROV

- Ballarat gold nugget drawings - Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer, 11 Oct 1853. Trove

- Alluvial Mining Model - Daisy Hill. Model by C.E. Nordstrom. 1858. Museums Victoria

- Road in the Black Forest 1852. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- The digger's road guide to the gold mines of Victoria and the country extending 210 miles round Melbourne. Gilks, Edward. 1853. State Library Victoria

- View of Hobart Town, Van Diemens Land. Lycett, Joseph, engraver. Published by J. Souter, 1824. State Library Victoria

- Australia Felix, or, District of Port Phillip. W. & A. K. Johnston. 1848. State Library Victoria

- Glorious News! Separation at last! Melbourne Morning Herald printer. 1850. State Library Victoria

- Golden Point, Mt. Alexander. Engraved by Thomas Ham. 1852. State Library Victoria.

- Ballarat looking N W from Mount Buninyong. 1855. State Library Victoria

- Country between Navarre and Ararat. 1857. PROV

- Topographic feature map of Stawell Goldfield area. Undated. Geological Survey of Victoria

- Mining Model - Surfacing & Puddling, Shallow Alluvial Workings, Victoria, circa 1857. Carl Nordstrom. Museums Victoria

- Fossicking. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- Marking the claim, 1852. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- A Good Day's Work. Mason, Cyrus. 1855. State Library Victoria

- Diggers on way to Bendigo. S.T. Gill. 1869. State Library Victoria

- The Sundowner and his doings. Sleap, F. A. Melbourne: David Syme and Co. 1885. State Library Victoria

- Animation of the hand powered stamper and berdan pan. Michelle Ross.

- Diggers night camp 1852. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- The Gold Rush in Victoria. Calvert, Samuel. David Syme and Co. 1888. State Library Victoria

- Painting - Quartz Reefs, Stawell in 1859. W.J. Rees. Held by the Northern Grampians Shire Council

- Chilean mills for the processing of gold ore. Gustave-Adolphe Chassevent-Bacques. 1862. Wikimedia commons.

- Quartz crushing and amalgamating mill. Grosse, Frederick, engraver. George Slater 1857. State Library Victoria

- The Gipps Land Exploration Party - Discovery of a quartz reef. Ebenezer and David Syme 1864. State Library Victoria

- The Quartz Reef Pleasant Creek from the hill back of Messrs Blunder, Wainwright & Cos Camp. Edward Roper. 1857. State Library Victoria

- Township of Stawell, 1863. State Library Victoria

- The Reefs Hotel Pleasant Creek. 1858 - 1861. Stawell Historical Society

- Special allotments, Reefs, Pleasant Creek, Parish of Stawell. 1866. State Library Victoria

- Pleasant Creek Quartz Mining Co. Mount Ararat Advertiser and Chronicle for the District of the Wimmera Vic 1857 - 1861, Tuesday 7 May 1861

- Stawell, Panorama 1866. Supplied by Stawell Historical Society.

- Great Northern Mine. Mitchell Library of NSW

- Panorama of Stawell, 1874. Supplied by Stawell Historical Society

- Pleasant Creek Cross Reef. William Tibbits. State Library Victoria

- Gold miners operating steam crushing machine, chillian rollers and eight stamps at Pleasant Creek, Victoria, 1858. R. W. Jesper. National Library Australia

- Quartz Mine & Treatment Works Model - Port Phillip & Colonial Gold Mining Co. Clunes, Victoria. 1858. Carl Nordstrom. Museums Victoria

- Map of the Borough of Stawell. 1870. Geological Survey of Victoria

- Survey of Stawell gold mines. 1878. Geological Survey of Victoria

- Underground survey of the principal mines at Stawell. 1879. State Library Victoria

- Explosion de grisu en una mina francesa. 1892. Wikimedia Commons

- Sketches in the Garden Gully United mine, Sandhurst. Alfred Martin Ebsworth 1882. State Library Victoria

- Stawell gold field. Lithographed by E.R> Morris, Printed by J. Finnie and G. Lusty, Mining Department. 1878. State Library Victoria

- Underground workings of the New North Clunes Mining Company. Ebenezer and David Syme. 1873. State Library Victoria

- Gold at last! Ebenezer and David Syme. 1874. State Library Victoria

- Underground Mining - Crib Time. David Syme and Co. 1884. State Library Victoria

- Quartz mining - The Great Extended Hustler's Mine, Sandhurst. 1873. State Library Victoria

- Vertical Section, Learmonth's Claim, Egerton - Putting in a shot and clearing a heading. Ebenezer and David Syme. 1869. State Library Victoria

- Underground Workings - Miners at dinner. Ebenezer and David Syme. 1869. State Library Victoria

- The Creswick Mining Disaster - Scene at the head of the shaft. State Library Victoria

- The Duke and Timor Mine, Maryborough - Scene of the recent accident. State Library Victoria

- Identifying the dead. 1881. State Library Victoria

- Creswick mining disaster. 1882. State Library Victoria

- Convivial Diggers in Melbourne 1853. S.T. Gill. 1872. State Library Victoria

- Stawell Miners Right - Gaston Renard Rare Books

- Digging life twenty-five years ago. Alfred May and Alfred Martin Ebsworth. 1879. State Library Victoria

- The Stawell Jumpers. Calvert, Samuel. Ebenezer and David Syme. 1873. State Library Victoria

- The trial of Edward Kelly, the bushranger. Alfred May and Alfred Martin Ebsworth. 1880. State Library Victoria

- Map of Stawell Goldfield, showing Mining Leases, reefs, shafts and dykes. Parish of Stawell. Birch, G. G. Undated. Geological Survey of Victoria

- The Magdala Mine, Stawell. Ebenezer and David Syme. 1875. State Library Victoria

- Magdala Gold Mine, Stawell. Transverse section through Magdala shaft. Geological Survey of Victoria.

- Magdala-Cum-Moonlight Company Mine, Stawell. Transverse section to 1663 foot level. Birch G. G. Undated. Geological Survey of Victoria

- George Lansell. Foster & Martin. ca. 1880. State Library Victoria

- Plan and section of Lansells No 180 Mine, Sandhurst. 1890. Geological Survey of Victoria

- Plan of lands held under leases for gold mining at Stawell. 1885. Geological Survey of Victoria

- Magdala cum Moonlight Mine Workers c1890. Stawell Historical Society

- Magdala-cum-Moonlight poppet head, 1886. Supplied by Stawell Historical Society

- Magdala cum Moonlight Mine Poppet Head 1899. Stawell Historical Society

- North Cross Reef mine in Stawell - Sketches. Stawell Historical Society

- Underground photos of the Magdala-cum-Moonlight Mine. Geological Survey of Victoria

- Plan of the leased ground of the Magdala-Cum-Moonlight Company Mine, Stawell. Bate, J.H. 1899. Geological Survey of Victoria

- A drive in the Oriental Company's Mine, Stawell. Ebenezer and David Syme. 1878. State Library Victoria

- North Cross No. 1 Oriental Battery 1895. Supplied by Stawell Historical Society

- Stawell Mining Scene from Big Hill. c1890s. Stawell Historical Society

- Gold mine at Stawell. Supplied by Stawell Historical Society

- Sloanes & Scotchman Mining Co 1899. Stawell Historical Society

- Crown Cross and Sloans and Scotchmans. 1890s. Supplied by Stawell Historical Society

- Stawell Amalgamated Scotchmans Battery and Cyanide Plant. 1900. State Library of Victoria

- Cr. Thomas Kinsella 1800s. Studio Portrait. Stawell Historical Society

- Sloans and Scotchman's Mine, Stawell. Composite level plan. Allan, R. 1901. Geological Survey of Victoria

- Sloans and Scotchman's photos. Supplied by Stawell Historical Society

- Chilean mill wheel photos, 1983. Stawell Gold Mines.